From Surviving to Thriving – Ensuring the Golden Years Remain Golden for Older Women

The economic insecurity of older women affects us all—our neighbors, our friends, our coworkers, our families, and our society as a whole. This brief explores the drivers of economic insecurity for older women and sets forth a number of strategies and promising practices for funders to consider which address the needs of older women. Doing so will ensure this generation and future generations of men and women in this country can age financially secure and with dignity.

This publication is the fourth in a series of briefs that build on AFN’s publication, Women & Wealth, to explore how the gender wealth gap impacts women, particularly low-income women and women of color, throughout their life cycle, and provides responsive strategies and best practices that funders can employ to create greater economic security for women.

Download the new brief to learn more. READ EXCERPTS BELOW

AN OVERVIEW

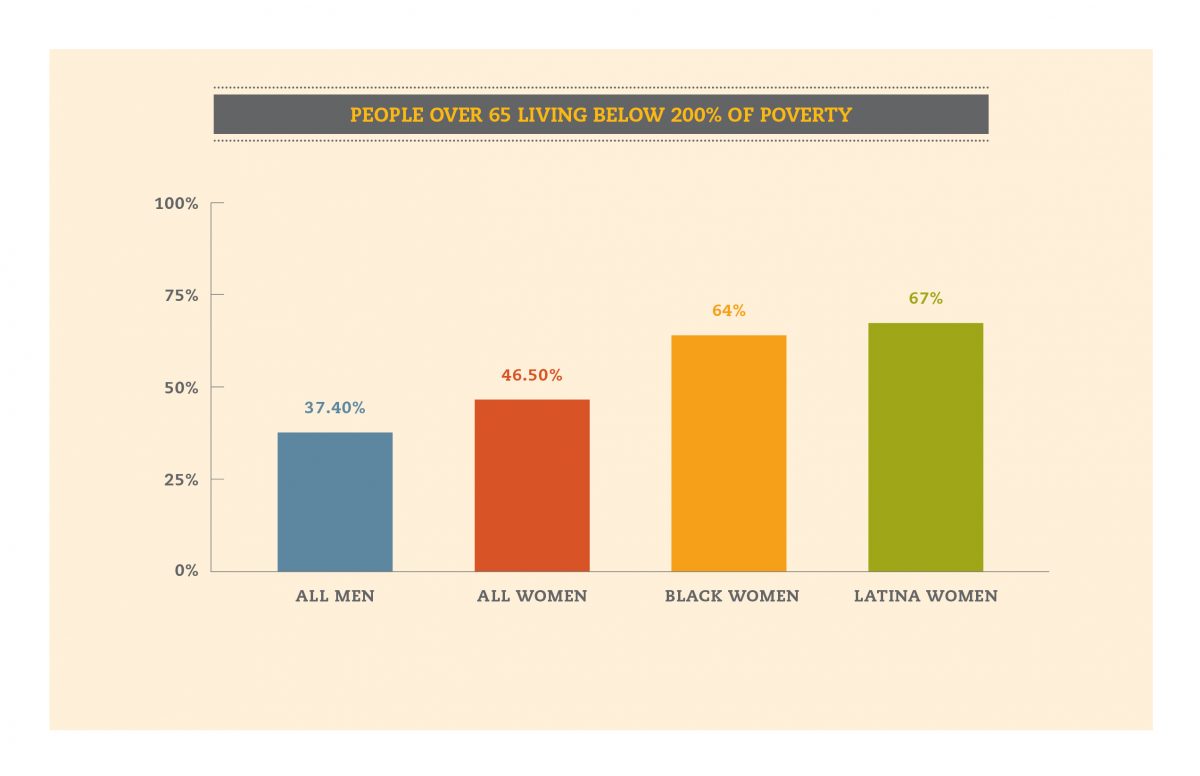

Over 27 million women, aged 65 and older, live in the United States. These older women face increasing challenges to remain economically secure as they age, and a significant number of older women find themselves unable to avoid living at or near poverty. In fact, 4.2 million women aged 65 and over live in poverty, according to the Supplemental Poverty Measure.

DRIVERS OF ECONOMIC INSECURITY

The primary drivers of economic insecurity for older women are summarized below. These drivers arise and compound across a woman’s lifespan, leading to increased insecurity in a woman’s later years. Each generation also faces specific financial and economic crises or events that affect their well-being in the future. On Shaky Ground, AFN’s initial brief in the series exploring opportunities to close the women’s wealth gap, described the Great Recession’s foreclosure crisis and its impact on women currently aged 45-65. It also discussed the influence of some of the drivers in this paper. That age cohort, for example, will be less economically secure as they enter retirement, which will compound the effect of the drivers described in detail below.

Inequitable Income

Women today are paid 80 cents to every dollar a man is paid, representing a 20% wage gap between men and women.10 The wage gap was much wider, however, during the decades in which older women today were participating in the workforce. In the 1970s and 1980s, the wage gap was between 30-40%. It was not until after the 1990s that the wage gap decreased to below 30%, and only for select populations.

Low Paying Work and Sex Discrimination

For women aged 55 and older without a college degree, nearly half (48%) are in jobs that pay $15 or less an hour compared to 29% of their male counterparts.13 Even in higher paying professions, jobs that women historically perform are compensated at lower amounts than jobs historically performed by men—despite these jobs requiring comparable skills and education.14 A college education does not ensure a higher paying job for women over 55. Older women with college degrees are twice as likely as college-educated men to work in low-wage jobs (22% compared to 11%).

Long term unemployment and the Great Recession

The Great Recession had long-term impact on women 55 and over— all of whom are now over 65. The long-term unemployment rate for women in this age cohort doubled between 2007 and 2011, from 3% to 6.1%.18 The length of time it took them to regain employment was longer (53.8 weeks) compared to younger women (41.4 weeks), often depleting any assets they may have accumulated.19 Employers were reluctant to hire older workers for various reasons including anticipated high health care expenses, expectations that older adults want higher compensation, and beliefs that older workers would be dissatisfied working for younger supervisors or that they may not work that long before retiring.20 Accordingly, many older women who eventually were able to secure work again did so by taking positions that paid less and provided fewer benefits than their employment prior to the recession.21 As a result, depleted assets were not likely to be rebuilt. Thus, in addition to experiencing the wage gap and sectoral segregation, the Great Recession helped make many more women currently over 65 economically vulnerable.

Unpaid Caregiving

Another driver of economic insecurity is that women in the United States continue to act as the primary, unpaid caregivers for both children and aging relatives and friends. To provide caregiving, women are likely to take time out of the workforce, reduce their work hours, or choose to work in lower paying jobs with different or more flexible hours.22 All of these scenarios have a negative cumulative effect on their household and retirement savings.

Lower Retirement Income [download to read in detail]

Racial and Ethnic Inequity [download to read in detail]

Financial Exploitation [download to read in detail]

RETIREMENT STABILITY: SOURCES OF INCOME AND WEALTH

Stable retirement is threatened by the drivers of economic insecurity because they compound over a woman’s lifetime, limiting both the income and accumulated wealth available in older age. A lifetime of lower wages limits retirement income from savings, pension, and Social Security, and increases the likelihood of needing means-tested income supports.

Limited and fixed retirement income coupled with a lack of assets or wealth means an increased likelihood of economic insecurity for women as health costs, housing costs, and inflation continue to increase annually. Work after age 65 can supplement income, but it gets harder to perform and secure work as the years pass. The lack of accumulated wealth or of home equity is particularly important since these represent funds to draw upon to supplement their income as people find themselves unable to work or as they get older. Without wealth, taking on increased debt to make ends meet exacerbates the precariousness for older women, who not only have a longer life expectancy than men, but are more likely to be unmarried as they age, further reducing their income. Further, women over 65 years of age are more likely to experience a disability that prevents them from working as they get older and may make them more susceptible to fraud and abuse.

STRATEGIES FOR ACTION & PROMISING PRACTICES

STRATEGIES FOR ACTION & PROMISING PRACTICES

To impact the economic insecurity faced by older women, it is critical to address the problem holistically.

Specifically, there is a need to identify services and supports that help older women become truly economically secure, and include their health care, housing and nutritional needs, and other essentials. Similarly, we need to better understand where these current supports and services fall short.

Any recommendations would be incomplete without understanding and recognizing the systemic effects of a lifetime of discriminatory treatment. We must define and address the reasons, policies and practices contributing to and reinforcing the higher rates of poverty, poor health, and financial distress that a significant number of women experience as they age. Systemic discrimination, whether it is based on race, gender, age, or other factors, is a large part of the problem older women face in their struggle for economic security.

The following sections highlight policy solutions, best practices, and innovative ideas for funders, policy advocates, government agencies, and practitioners interested in supporting this cohort of older women to not only become economically more secure, but also to enable them to pass along their heard-earned assets to future generations.

STRATEGY FOR ACTION: Support research examining and promoting better measurement of the economic security of older women

Download now to continue reading.